Throughout history, humanity has blended cultures to create endless variations in food, language, and fashion, but one dark constant remains: our capacity for brutality. In the Middle Ages, public executions and tortures were spectacles enjoyed by crowds, with devices designed to inflict unimaginable pain. Among them, the Spanish Donkey—also known as the Wooden Horse or chevalet—stands out as one of the most horrific. Used by the Holy Inquisition and later spreading to the Americas, this triangular wooden contraption turned punishment into a slow, agonizing death. This analysis explores the Spanish Donkey’s origins, design, variants, and devastating effects, shedding light on a grim chapter of human cruelty.

The Spanish Donkey exemplifies the sadistic ingenuity of medieval torture, blending psychological humiliation with physical agony. Emerging during the Inquisition and enduring through colonial times, it was a tool of control, punishment, and spectacle. Let’s delve into its design, historical use, variants, and the permanent horrors it inflicted on victims, while reflecting on its place in the evolution of human rights.

Origins and Design: A Deceptively Simple Horror

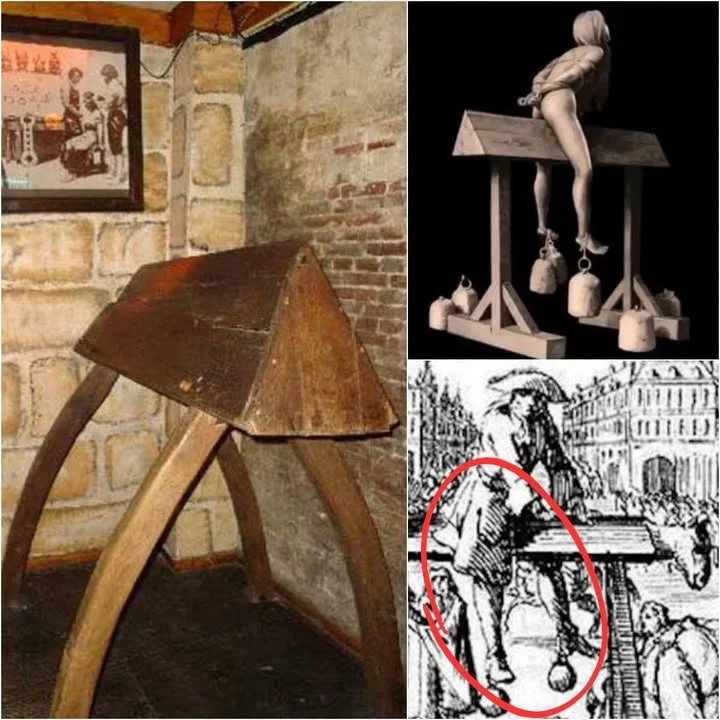

The Spanish Donkey, allegedly invented by the Holy Inquisition in 12th-century France, was a wooden triangular frame with a sharp ridge mimicking a horse’s back. Constructed from planks nailed together, the device stood 6–7 feet (1.8–2.1 meters) high on four legs, often with wheels for mobility and a horse-like head and tail for mockery. The sharp apex—sometimes enhanced with metal spikes—formed the “saddle” where victims were forced to straddle. Hands tied behind their back, ankles weighted with irons or muskets, victims bore their full body weight on their genitals or perineum. Professor Darius Rejali, in Torture and Democracy, describes it as “a large trestle with a sharp ridge… The handcuffed prisoner straddled the ridge that dug into the cleft between his legs.” An X post from HistoryUnveiled captured its terror: “The Spanish Donkey wasn’t just torture—it was a public spectacle of slow death.”

Reserved for “deviant Christians” like heretics or the faithless, it spread to Spain, Germany, and the Americas via Jesuit missionaries. By the 17th century, it was documented in colonial Canada, and even U.S. Founding Father Paul Revere ordered its use in 1776 against Continental Army soldiers for playing cards on the Sabbath. The Spanish army continued its use into the 1800s, highlighting its enduring appeal as a tool of religious and military discipline.

The Spanish Donkey or Wooden Horse Source: eremit08 / Adobe Stock

Variants and Global Spread: From Inquisition to Colonial Cruelty

The Spanish Donkey evolved with cultural adaptations, but its core principle remained: maximizing pain through gravity and time. In Europe, it was often public, with victims “riding” for hours or days in town squares, their suffering a spectacle for crowds. The English and Dutch colonists brought it to America, where a 12-foot-high version with sharpened edges stood in downtown New York. Variants included “riding the rail,” where offenders straddled a fence rail carried through town, sometimes tickled with feathers for added humiliation. During the American Civil War (1860s), it punished infantry for infractions like drunkenness or cursing, with accounts describing victims “riding bareback for two hours daily, with weights on their feet until fainting from pain.” An X post from DarkHistoryFacts noted, “From Inquisition racks to Civil War rails—the Donkey’s variants were as cruel as they were creative.”

The Jesuits, notorious for violence, introduced it to Canada in 1646, using it on indigenous peoples and settlers alike. In the U.S., metal spikes were added to amplify agony, ensuring genital mutilation. These adaptations reflected the device’s migration: from religious purification in Europe to colonial control in the Americas, where it enforced social order through terror.

How It Worked: Permanent Mutilation and Death

The torture’s mechanics were brutally simple. Victims, often stripped naked for humiliation, were mounted with legs spread over the sharp ridge, hands bound, and weights (up to 100 pounds) on ankles to pull them down. Gravity did the rest: the victim’s weight pressed their genitals or perineum onto the edge, causing excruciating pain as flesh tore. For men, ruptured scrotums and split-open genitals were common; for women, it destroyed reproductive organs, causing infertility. A ruptured perineum and broken sacrum (the triangular bone at the spine’s base) ensured survivors could never walk normally again. An X post from MedievalTorture quoted Rejali: “Guards tied muskets to the legs to strain the thighs—very few could walk after this hellish torture.”

Punishments lasted hours to days, leading to bleeding, infection, or death. In extreme cases, added weights split victims in half. During the Civil War, one account described: “The legs were nailed to the scantling… making it very painful, especially with heavy weights fastened to his feet and a large beef bone in his hand.” Victims often fainted from pain, only to be revived for more suffering. The psychological torment—public humiliation and helplessness—amplified the physical agony, making the Donkey a tool of both body and mind destruction.

Ethical and Historical Reflections

The Spanish Donkey’s use reveals humanity’s dark fascination with spectacle. Rooted in medieval Europe’s public executions, it satisfied crowds’ voyeuristic thrill in others’ pain, often justified as moral or religious punishment. As societies evolved, such devices became symbols of barbarism, leading to their prohibition under international treaties like the Geneva Conventions and the UN Convention Against Torture. Yet, torture persists in modern conflicts, flouting these laws. An X post from HumanRightsWatch stated, “The Spanish Donkey’s disappearance is progress, but torture today shows we haven’t learned.”

The device challenges us to confront our ancestors’ cruelty and question how far we’ve come. While democratic societies condemn it, its legacy reminds us that brutality can resurface without vigilance. Education and human rights advocacy are essential to ensure such horrors remain in the past.

Spanish Donkey stands as a chilling testament to medieval ingenuity in inflicting pain and the human capacity for cruelty. From its Inquisition origins to colonial variants, this device mangled bodies and spirits, leaving victims permanently scarred or dead. Its disappearance from modern lexicons reflects progress in human rights, but the persistence of torture today serves as a warning. As we reflect on this horrific invention, let’s commit to a world where such devices are relics of a barbaric past. What lessons from history like this resonate with you?