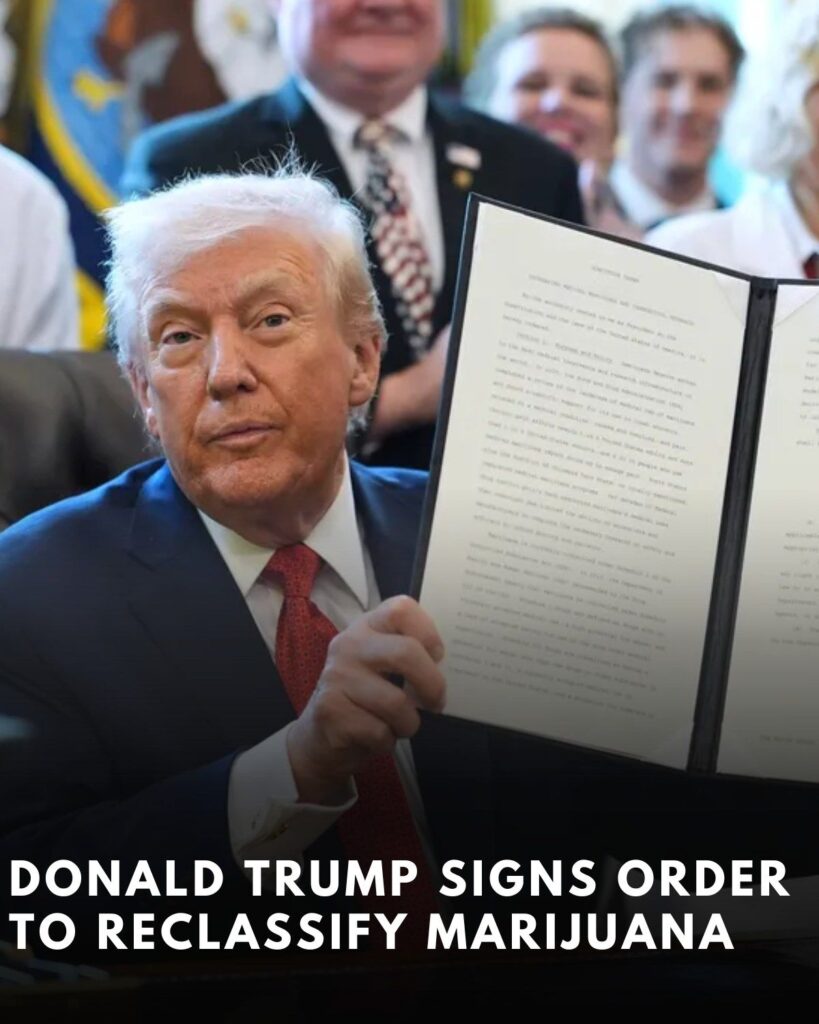

President Donald Trump has signed an executive order directing his administration to pursue moving marijuana into a less restrictive category under US federal drug law, a step the White House framed as a shift towards recognising medical use while maintaining federal controls on cannabis.

The order, signed on 18 December, instructs the attorney general to “fast-track” the process of reclassifying marijuana as a Schedule III substance under the Controlled Substances Act, according to the text released by the White House.

If completed, the change would move marijuana out of Schedule I, the category reserved for drugs deemed to have a high potential for abuse and no accepted medical use, and into a tier that federal regulators treat as having accepted medical value and a lower risk profile than Schedule I or II substances. Schedule III includes drugs such as ketamine and some products containing codeine, and is subject to controls including limits on prescriptions and recordkeeping.

The White House order also places emphasis on expanding scientific research, directing federal agencies to increase and streamline research into medical marijuana and cannabidiol, commonly known as CBD. The text sets out policy goals focused on “increasing medical marijuana and cannabidiol research,” with the administration arguing that research barriers have limited the evidence base used by doctors, regulators, and patients.

The move is expected to be welcomed by parts of the legal cannabis industry and some patient advocates, who have long argued that Schedule I status makes research more difficult and increases costs for regulated businesses operating under state law. Industry analysts have also said rescheduling could change the tax treatment of cannabis companies by eliminating the impact of a federal tax provision known as Section 280E, which prevents businesses trafficking Schedule I or II substances from taking standard business deductions.

However, the order stops short of legalising marijuana nationwide. Even if marijuana is placed into Schedule III, it would remain a controlled substance at the federal level, and non-medical use would not become legal simply as a result of rescheduling.

The decision also lands in the middle of a policy process that began under President Joe Biden. The Biden administration launched a formal review of marijuana’s federal status, leading to a proposed rule to move it to Schedule III and a public comment period that drew tens of thousands of submissions, according to reporting and legal analyses tracking the process.

The Drug Enforcement Administration, which has a central role in scheduling decisions under federal law, had been moving through the administrative steps. A hearing on the proposed rescheduling that had been scheduled to begin in January 2025 was postponed pending the resolution of an appeal in the proceedings, the DEA said at the time, illustrating how the process can be delayed by litigation and procedural challenges.

Reuters reported that Trump’s order directs the attorney general to advance the reclassification and is intended to ease certain federal restrictions, potentially opening up more research and changing aspects of how the industry is regulated. The report said the announcement prompted an immediate, if mixed, reaction among investors and political leaders, with supporters arguing the change reflects medical realities and critics warning it could encourage drug use.

The rescheduling process is technically complex and typically involves coordination among federal health agencies, the justice department, and the DEA. Public health officials assess scientific evidence on medical uses and risks, while law enforcement agencies weigh factors such as diversion and abuse potential. The White House order’s focus on “fast-tracking” suggests the administration wants to reduce the time between agency review and a final scheduling decision, but it does not remove the legal requirements that govern rulemaking.

Legal and industry specialists have said a Schedule III classification, if implemented, could reshape the economics of the state-legal cannabis market by changing tax burdens that have contributed to thin margins for many operators. Analysts have also pointed to potential knock-on effects for research institutions, drug development, and pharmaceutical regulation, given that Schedule III substances can be prescribed under federal rules and are typically easier to study than Schedule I drugs.

At the same time, experts have cautioned that rescheduling alone is unlikely to resolve one of the industry’s biggest problems: access to mainstream banking. A separate Reuters analysis published after the order said cannabis companies could still face major hurdles securing services from large banks because marijuana would remain illegal at the federal level outside tightly regulated channels, leaving institutions wary of legal and regulatory risk.

The administration’s move reflects a broader national shift in cannabis policy that has unfolded over decades, with a growing number of US states legalising marijuana for medical use, recreational use, or both. Federal law, however, has not kept pace with state reforms, creating a patchwork system in which companies can operate legally under state statutes while remaining exposed to federal enforcement and regulatory uncertainty.

The White House order also arrives amid continued debate over how federal policy should treat CBD and other cannabinoid products that have become widely available in consumer markets. While some CBD products are regulated as medicines, others are sold as supplements or wellness products, and regulators have repeatedly warned about mislabelling and unverified health claims. The executive order’s emphasis on research is likely to be used by officials as justification for clearer rules governing product safety and medical evidence.

In practical terms, the next steps will centre on federal agencies translating the presidential directive into formal regulatory action. That typically involves drafting and publishing rulemaking documents, responding to public comments, and issuing a final rule that can still face court challenges. The DEA’s earlier postponement of a hearing in the Biden-era scheduling process underscored how procedural disputes can slow the timeline, even when the direction of travel appears set by political leadership.

For patients and doctors, the outcome could be significant but uneven. A Schedule III classification may help expand clinical research, potentially strengthening the evidence base for certain medical uses, but it would not automatically change state-level eligibility rules, medical programme access, or the legality of recreational cannabis. The order’s framing, in both the White House text and subsequent reporting, emphasised medical research and regulatory adjustment rather than broad decriminalisation.

As the federal government moves towards a revised stance, the political argument is also likely to intensify over what rescheduling should mean in practice, including how it intersects with criminal justice enforcement, workplace drug policies, and impaired driving laws. The executive order sets a clear intent to change marijuana’s status within the federal drug schedule, but it also signals that the administration is seeking a narrower outcome than full legalisation, leaving major policy battles for Congress, regulators, and the courts.