The Day Paradise Lost Its Innocence: The Untold Nightmare of Sian Kingi

Noosa Heads, Australia. Picture a place where the sun seems to shine a little brighter, where the rhythm of the crashing waves sets the tempo for a life that feels perpetually on vacation. It’s the kind of town where doors are left unlocked, where neighbors know each other by name, and where the concept of “stranger danger” feels like a distant rumor from a big, scary city. In 1987, Noosa was the jewel of Queensland’s Sunshine Coast—a sanctuary of surf, sand, and safety. It was a paradise. But as any true crime aficionado knows, even paradise has its shadows. And on one sweltering November afternoon, a shadow stretched across this coastal haven that would never truly lift.

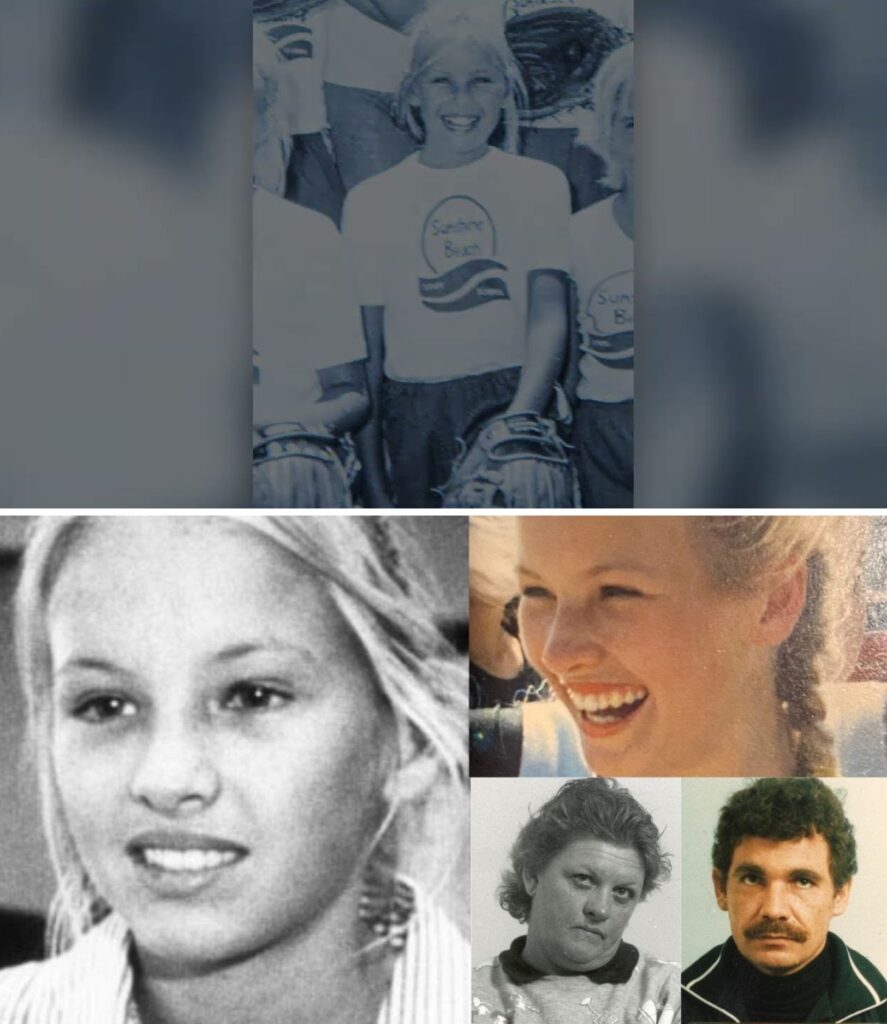

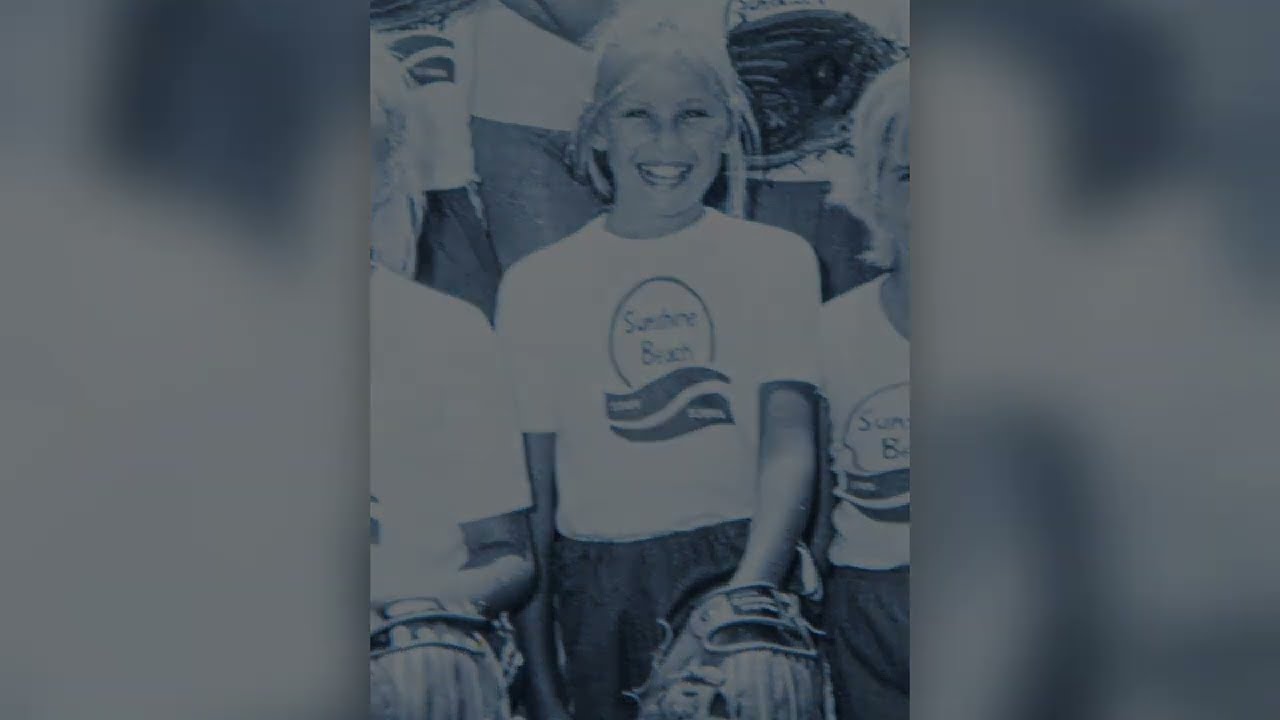

The date was Friday, November 27, 1987. The air was thick with the anticipation of the weekend. For 12-year-old Sian Kingi, it was just another Friday. Sian was the kind of girl who made you believe in the goodness of the world. With her Maori heritage, she possessed a striking natural beauty, but it was her personality that really grabbed you. She was shy, yes, known for a quiet demeanor that made her fierce love for dance all the more surprising. When she danced, she came alive. And her smile? It was the kind of smile that could light up a room, a cliché that, in Sian’s case, was heartbreakingly true. She was a good kid, a helpful daughter, and a star on her volleyball team.

That afternoon, Sian had met her mother for a mundane, everyday errand: grocery shopping. They navigated the aisles, chatting about school, about dance, about the little things that make up a 12-year-old’s world. They packed the bags into the family car, but there was a snag. Sian had ridden her bicycle to school that day. The trunk was full of groceries; the bike wouldn’t fit. It was a small logistical hiccup, the kind that happens in families every day. Sian, independent and helpful, suggested a simple solution: she would ride her bike home.

It wasn’t a long ride. She knew the streets of Noosa like the back of her hand. She rode this route every single day. Her mother, trusting the safety of their community and her daughter’s competence, agreed. “I’ll see you at home,” might have been the last words they exchanged. A casual promise of a reunion that would never happen. As Sian’s mother drove away, she watched her daughter hop onto her bright yellow bicycle and pedal off into the late afternoon sun. It should have been a 15-minute ride. It became a journey into a nightmare that has haunted Australia for over three decades.

When Sian’s mother pulled into their driveway and unpacked the groceries, the house was quiet. Too quiet. She checked the time. Sian should have been just a few minutes behind her. At first, there was no panic—just the mild annoyance of a parent wondering if their child dawdled. Maybe Sian had bumped into a friend from school? Maybe she had stopped to chat with a teammate from volleyball? It was a small town; these things happened. But as the minutes ticked by, turning into half an hour, then an hour, that mild annoyance began to curdle into a cold knot of dread in the pit of her stomach.

She started making calls. First to the friends who lived along Sian’s route. “Have you seen Sian?” “Did she stop by?” The answers were all the same: No. No. No. The knot in her stomach tightened. She branched out, calling friends who lived further away, grasping at straws. By 8:00 PM, the sun had long since set, casting Noosa in darkness. Sian Kingi was afraid of the dark. She would never, ever stay out this late without calling. The reality of the situation crashed down on Sian’s parents with paralyzing force. They couldn’t wait by the phone anymore. They had to go out.

They retraced her steps. They drove slowly along the route she would have taken, scanning the sidewalks, the bushes, the shadows. And then, they saw it. In Pinaroo Park, a stretch of green just behind Sian’s school, lying abandoned on the side of a path, was a bicycle. It was bright yellow. There was no mistaking it. It was Sian’s. It was lying there as if its rider had just vanished into thin air. Seeing that abandoned bike is a parent’s primal nightmare realized. It was the moment hope began to fracture. They didn’t go home. They went straight to the police station.

In many missing children cases, especially in the 80s, police might have told the parents to wait 24 hours, suggesting the child had run away. But not this time. The Noosa police took one look at the terrified parents, heard the details of the abandoned yellow bike, and knew this was serious. They launched into action immediately. It was late, but they managed to wake up editors at the local newspaper to get Sian’s picture into the next morning’s edition. They weren’t taking chances. The officers, many of whom had daughters Sian’s age, took the case personally. They weren’t just cops; they were fathers.

The community of Noosa responded with an outpouring of love and terror. This didn’t happen here. Neighbors formed search parties, combing the beaches, the bushland, and the streets. Everyone was looking for the girl with the bright smile. For days, the town held its breath. They prayed for a runaway scenario. They prayed for a misunderstanding. They prayed for anything other than the truth. But as the days dragged on—one day, two days, five days—the silence from Sian became deafening. The hope that had buoyed the search began to dwindle, replaced by a grim resignation.

On December 3, 1987, six days after Sian waved goodbye to her mother, the search came to a devastating end. Her body was discovered in the Tinbeerwah Mountain State Forest, a dense, secluded area about 15 kilometers away from where her bike was found. The details of the discovery were enough to break even the hardest homicide detective. Bob Dallow, the man leading the investigation, would later say the image haunted him every single day. Sian was found fully clothed. She was still wearing her shoes. She was still wearing her pink socks.

It was those pink socks that shattered hearts across the nation. They were a symbol of her youth, her innocence, and the suddenness with which she was taken. Sian hadn’t just been killed; she had been subjected to a brutal, prolonged assault. She had been sexually assaulted, stabbed, and strangled. The perpetrators had left her there in the forest to bleed out, alone in the dark. It was a crime of such depravity that it seemed impossible that a human being could commit it. But the evidence at the scene told a story not just of one monster, but potentially two.

The investigation kicked into high gear. Police were desperate. They had a dead child, a terrified community, and a killer on the loose. But they also had leads. Witnesses at Pinaroo Park—the place where the yellow bike was found—remembered seeing something. A car. A white 1973 Holden Kingswood station wagon with interstate license plates. It had been prowling the streets. It was a specific description, and in a town like Noosa, out-of-town cars stood out. But at first, the connection seemed tenuous. Was it just a tourist? Or was it something darker?

Then, the pieces started to click together. Detectives looked at other recent crimes in the wider region, searching for a pattern. They found one. Just weeks earlier, on November 11, a woman named Cheryl Mortimer had a terrifying encounter in nearby Ipswich. She was driving home from work when she was flagged down by a woman in a car. The woman looked distressed, and Cheryl, being a good Samaritan, rolled down her window to help. She thought the woman needed directions. She was wrong.

As Cheryl leaned out, a man sprang up from the shadows. He lunged at her, pressing a knife to her throat. It was an ambush. Cheryl fought for her life. She struggled, kicking and screaming, refusing to be pulled from her vehicle. In the chaos, the attacker fumbled. He cut his own hand on the knife. The sight of his own blood seemed to spook him. He jumped back into his car—a white station wagon—and sped off with the woman. They left behind a shaken Cheryl and, crucially, a pool of the attacker’s blood. DNA.

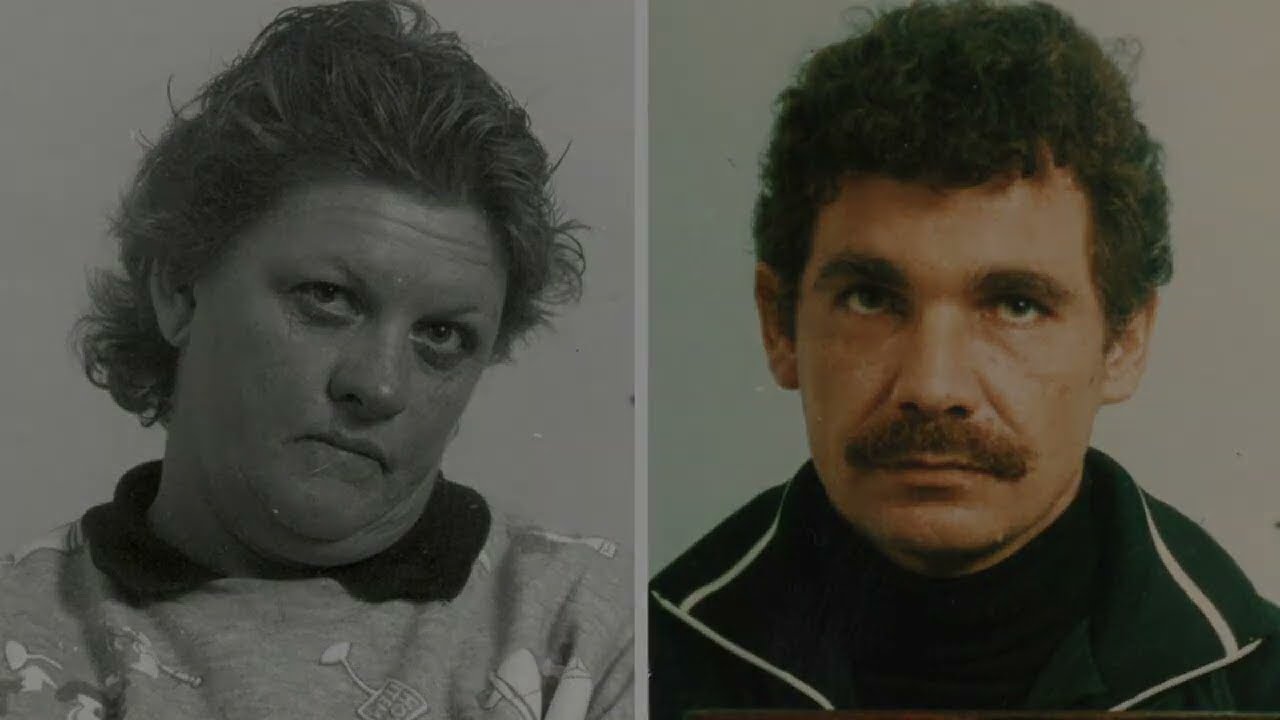

Police realized they were dealing with a pair. A man and a woman. A Bonnie and Clyde, but without the romance—just pure, distilled evil. The description of the car in Cheryl’s attack matched the car seen near Pinaroo Park. The white Holden Kingswood. Investigators traced the vehicle registration. It belonged to a woman named Valmae Beck. And her husband? A man named John Barry Watts. The net was closing in.

Valmae Beck and Barry Watts were not your average couple. Their union was a toxic collision of two damaged, dangerous pasts. Valmae had a life story that read like a tragedy from the start. The youngest of four in a poor family, she was working in a factory by age 12. By 15, she was a ward of the state, her parents deemed neglectful. She spent her youth drifting in and out of jail, accumulating ex-husbands and children she didn’t raise. By the time she met Barry, she had six children, none of whom lived with her.

Barry Watts was ten years her junior, but his darkness matched hers. An orphan and a ward of the state, he, too, had grown up in the system. He met Valmae in Perth in 1983, shortly after being released from prison. They married three years later, but it wasn’t a happy home. Barry was a man consumed by jealousy and twisted obsessions. He resented Valmae’s past relationships. He hated that she wasn’t a “virgin” when they met. This hatred festered, morphing into a sick fantasy. He wanted a young virgin to “replace” what he felt Valmae couldn’t give him. And Valmae? Desperate to keep him, terrified of being alone, she agreed to help him find one.

When police arrested the couple on December 15, 1987, the dynamic between them became immediately apparent. Barry Watts was a stone wall. He sat in the interrogation room, stoic, silent, giving nothing away. He had been down this road before. In fact, he had been tried for the murder of another woman, Helen Mary Finney, just a month prior, but was acquitted due to lack of evidence. He thought he was untouchable. He thought he could outsmart them again.

But Valmae was different. She was the weak link. Under the pressure of the interrogation, she cracked. She wanted to talk. She wanted to unburden herself. Investigators, sensing her need to shift the blame, let her talk. And what she said was enough to make your blood run cold. She didn’t just confess; she detailed the entire abduction with a chilling calmness. She told them how they had been hunting that day. How they were driving around, looking for a target.

She told them about the “ruse.” This is the part of the story that parents warn their children about, the detail that makes Sian’s death so universally terrifying. They saw Sian on her bike. They pulled over. Valmae got out. She didn’t try to grab Sian. She used Sian’s kindness against her. Valmae told the 12-year-old that she had lost her dog—a little poodle with a pink bow. She asked if Sian would help her look for it.

Sian, the girl who loved animals, the girl with the big heart, stopped her bike. She got off. She walked into the bushes to help this stranger find her pet. That was when Barry Watts struck. He grabbed her from behind. He threw her into the back of the station wagon. They tied her up. And then, they drove. Valmae drove the car while her husband tormented a terrified child in the back seat. They took her to the forest, and there, Barry lived out his depraved fantasy while Valmae watched and assisted.

Valmae’s confession was a goldmine, but the police knew Barry was the master manipulator. They needed to nail him, and they couldn’t rely solely on the word of an accomplice who might change her story in court. They needed a confession from Barry himself. They decided to play a dangerous game. They sent in an undercover officer.

Matthew Harry was a young cop, just 27 years old. He was tasked with the impossible: go into a cell with a monster, pretend to be a criminal, and get him to talk. For weeks, Harry lived with Watts. He ate with him, slept in the same cell, and listened to his breathing. It was a psychological torture test. Harry later described the urge to just “break his neck” every time he looked at Watts. But he held it together. He wore a wire. He recorded hours of conversation. He gained Watts’ trust.

And it worked. Watts didn’t give a tearful confession, but he said enough. He revealed details that only the killer could know. He bragged. He slipped up. When prosecutors played those tapes, the stoic mask of Barry Watts finally slipped. The jury heard the voice of a man with zero remorse, a man who viewed a child’s life as nothing more than a prop for his own gratification.

The trial was a sensation. The community wanted blood. When Valmae and Barry were led into court, crowds pelted the police vans with rocks. They screamed for the death penalty (which Australia had abolished). The details that came out in court were gruesome. Valmae tried to paint herself as a victim of Barry’s control, but the jury wasn’t buying it. She was an active participant. She lured the child. She drove the car. She held the knife.

In the end, justice was swift and severe. Both Valmae Beck and Barry Watts were sentenced to life imprisonment without the possibility of parole. It was the maximum sentence available. The judge made it clear: these two should never breathe free air again.

Life in prison was not kind to Valmae Beck. She was a child killer, the lowest of the low in the prison hierarchy. She was targeted instantly. In one particularly brutal incident, other inmates filled a sock with a tin can and beat her over the head with it, causing severe injuries. She spent the next two decades looking over her shoulder. Interestingly, she turned to religion, claiming to have found God. She even divorced Barry Watts from prison, publicly stating she regretted everything she had done for him.

Valmae died in prison in 2008. She had undergone heart surgery and was placed in a medically induced coma from which she never woke up. She died without family by her side, a lonely end for a woman who had caused so much loneliness. There were no tears shed by the public for Valmae Beck.

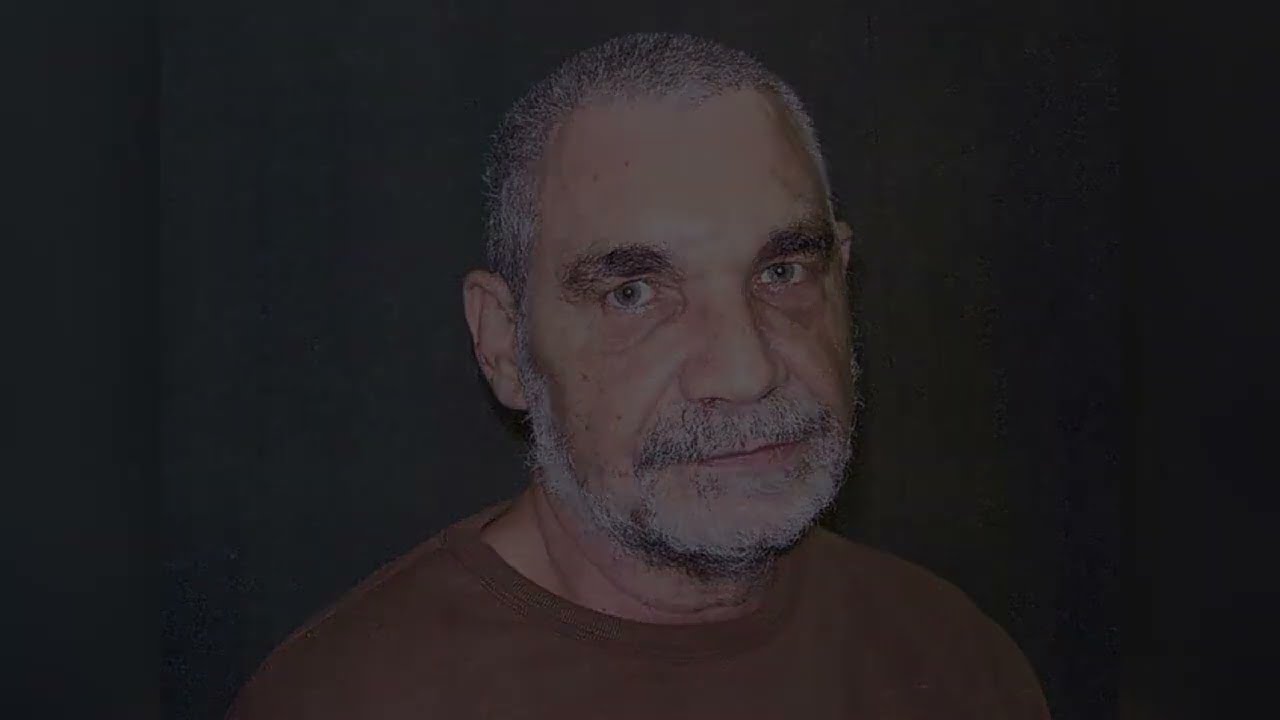

Barry Watts, however, is a different story. He is still alive. He sits in a cell in Queensland, an old man now. But age hasn’t softened the public’s hatred for him. In 2009, he applied for parole. It was a slap in the face to Sian’s family. The community rallied again, just as they had in 1987. Petitions were signed. Protests were organized. Alan Burke, one of the detectives on the original case, came out of retirement to make a statement. His words were sharp as a razor: “If they’d still had a hanging knot, I would have quite happily hanged both of them. I still would.”

Watts was denied parole. But the fear that he might one day be released persists. It sparked legislative changes in Queensland, dubbed “Sian’s Law,” designed to make it harder for the “worst of the worst” to get parole hearings, sparing families the trauma of reliving the crime every few years.

The legacy of Sian Kingi is not just a cautionary tale; it is a scar on the Australian psyche. It changed the way parents raised their children. The “lost dog” trick became the ultimate warning. But more than that, Sian is remembered. Every year, on the anniversary of her death, the community remembers the girl with the pink socks.

Online, the case continues to spark fierce debate and raw emotion. On true crime forums and YouTube comments, the sentiment is consistent and furious. “I remember this like it was yesterday,” one user wrote. “We were the same age. My mom never let me ride my bike alone again. Sian saved a lot of us because our parents got so strict.” Another comment reads, “The fact that she stopped to help find a dog… she was too good for this world. That kindness was weaponized against her. That creates a rage in me I can’t explain.” And regarding the perpetrators: “Valmae got off easy dying in a coma. Watts should never see the sun. Let him rot.”

The story of Sian Kingi is a reminder that evil doesn’t always look like a monster in a mask. Sometimes it looks like a distressed woman looking for a puppy. It’s a story of a town that lost its innocence, a family that lost their future, and a little girl whose yellow bike still leans against the fence of our collective memory.

As Barry Watts sits in his cell, the world has moved on, but it hasn’t forgotten. And as long as Sian’s name is spoken, as long as her story is told, the darkness will not win completely.

What do you think? Should “life” always mean “life” for crimes involving children? Do laws like “Sian’s Law” go far enough? Drop your thoughts in the comments below—let’s keep Sian’s memory alive.